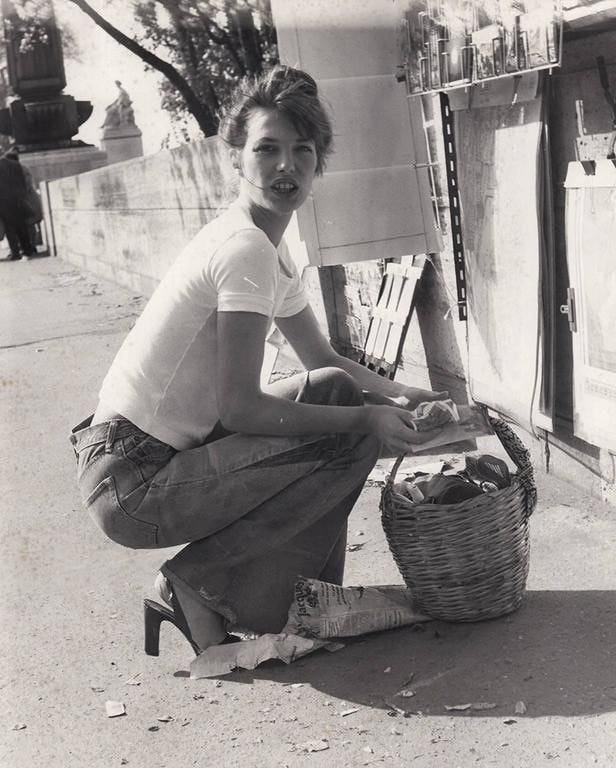

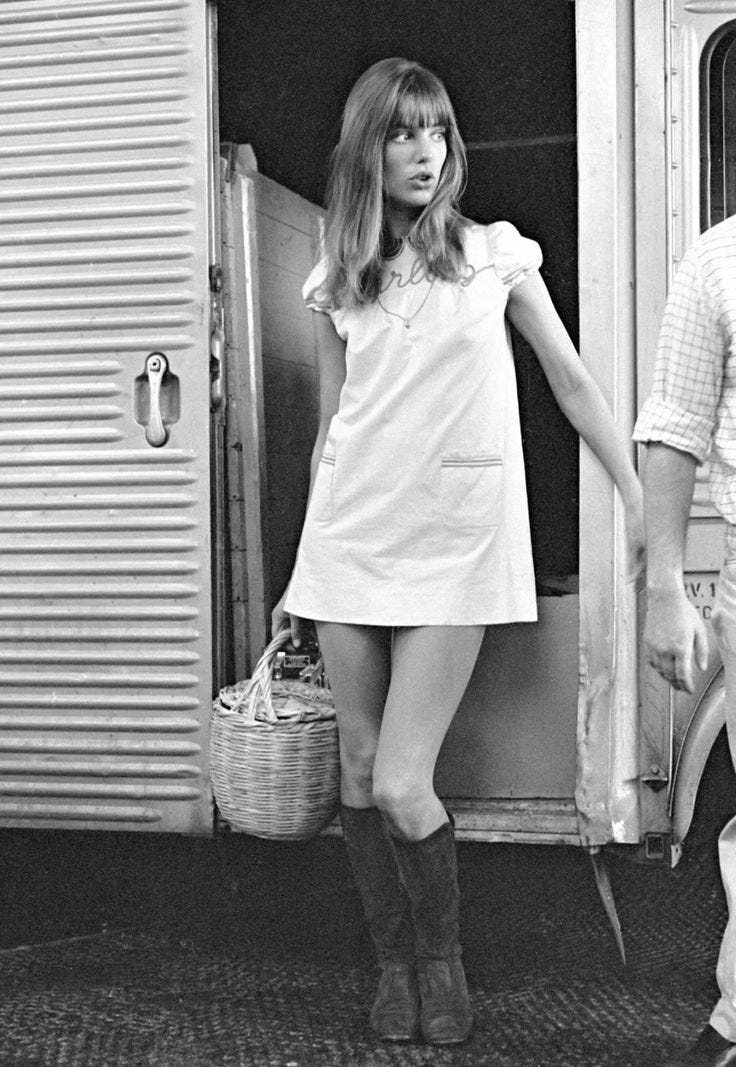

I am a girl with many muses, each of a tantalising je ne sais quoi. Take a photograph of Jane Birkin, for instance: a pair of classic flared denim jeans, a plain white short-sleeve tee, and her signature wicker basket hanging effortlessly from her fingertips. Her clothes were accessible, the kind you could easily replicate, but there was an ease about her that made her style feel so distinctly… her.

Today, the rise of influencers and shoppable post platforms like ShopStyle and Like to Know It have transformed style into something transactional. Our tastes are now guided by a highly tailored algorithm designed to present us with items it knows will strike a chord. With a single tap, the outfit we admired is already en route to our doorstep. Muses, by contrast, thrived on being out of reach. They had a faint smile and a sense of self that couldn’t be bought or bottled.

To mourn the death of the muse is, in many ways, to mourn the loss of style. Shopping for clothes was once an affair of the senses, an exercise in intuition where hours were spent scouring the rails. Today, dressing has become an exercise in imitation. It’s no surprise we discard our clothes so easily; they tell no story and bear no meaning. Style, at its very core, has never been a matter of mimicry. Just as designers draw inspiration from art, architecture, and textiles, I believe we too should lift ideas when we get dressed. A true muse is revered precisely because they do not resemble anyone else.

In the past, trends followed a 20-year cycle. Today, social media has rendered that rule obsolete. Gone are the days where mini skirts symbolised defiance against domesticity, safety pins embodied anarchy – à la Sex Pistols – and flares signalled resistance to the Vietnam War. Instead, the abundance of resources that technological advancements have brought forth have fostered a sense of stifling uniformity.

The fashion of the 60s and 70s belonged to an age less plagued by self-consciousness, when clothes were inextricably bound to music, design, politics, and seismic shifts in sexual freedom. The trouble with trends is their ability to hollow out that connection, to turn style into a game of follow-the-leader. Style ought to be a reflection of one’s own philosophy.

For me, the thrill of secondhand shopping lies in its unpredictability, a world away from well-coordinated lookbooks and rather predictable trends. Unlike the slick, seasonal displays of a contemporary store, a thrift shop invites you into a world brimming with garments from every conceivable era, designer, and style. It demands time — a luxury in itself — patience, and a touch of luck. Sometimes, it’s little more than the feel of a fabric or a peculiar shade that pulls you in.

Xo

Gracie, Founder of Worn